Art in Lent 3: Suffering

I don’t often find images of the suffering of Christ very helpful in my contemplation of the Passion. They are either so gruesome that I find my eyes fixating on the details of suffering, losing the meaning in the process of this individual death; or else the Christ they show is sweet, silent, almost cloying in his innocence. I lose the sense of God choosing the path of sacrifice. I worry that the Man of Sorrows no longer has a choice.

In addition there are cultural difficulties. Images of the cross are now specific to that one death in our minds: it is easy to forget that, under Roman occupation, crucifixion was reasonably common, and associated with the lowest in society – the thieves and murderers, the scum, for whom it was important that the form of execution was not only agonizing but also degrading. Indeed, Christ was not portrayed on the cross in Christian images until many years after his death, such were these associations at the time. However painful to look at, many images of Christ’s crucifixion are a relatively pretty and dignified version of the truth. In reality there was no heavenly light or glowing halo; no protective loincloth; no dramatic raised head or meaningful looks. Only the agony, the panting breath, the splintering wood, the searing nails, the scorching thorns, the naked public defaecation, the burning muscles, the few gasped out words before death. And what of the face of Christ? How do I relate to a sixth century icon, a painting by a Flemish master, a Victorian allegorical work, a twentieth century film? What about those from more alien cultures to our own – from Mexico, from Japan, from Ethiopia? How can I find Christ, through such variety?

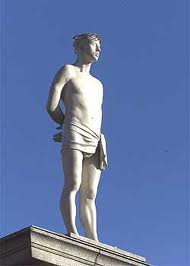

I find that simplicity is helpful; hence my choice of ‘Ecce Homo’ by Mark Wallinger (1999).

Ecce Homo: behold the man.

Then Pilate took Jesus and had him flogged. And the soldiers wove a crown of thorns and put it on his head, and they dressed him in a purple robe. They kept coming up to him, saying, "Hail, King of the Jews!" and striking him on the face. Pilate went out again and said to them, "Look, I am bringing him out to you to let you know that I find no case against him." So Jesus came out, wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe. Pilate said to them, "Here is the man!" John 19: 1-5

In the KJV v5 is translated as ‘Behold the Man’; after questioning him, and receiving no answer that convinced him of Jesus’ guilt, Pilate echoes this in verse 14 with ‘Behold the King’. These are ambiguous words. Pilate could be accusing – either the crowd or Jesus; pleading – for the crowd’s mercy; or even worshipping. So too is this sculpture ambiguous. It is startling in its simplicity: a pure white man, life-size, with no seams associated with life-casting. Every last skin bump and pit is shown. The eyes are closed, in subjugation; does the knowledge that they had to be closed because of the process, the way the model had to wait entombed in resin, change the way we respond? He is naked, save for a small loincloth; Wallinger has not chosen to depict the robe; but the crown is there. This is a Christ someway between the twin pronouncements of Pilate, between ‘Behold the man’ and ‘Behold the king’. He is both. He is neither.

The crown of thorns is gently gilded, echoing the shining haloes of the icons of the past. This Christ has been afforded a golden crown, a sign of kingliness, the gold that was given to him at birth and is his by rights – now painfully pressed into his skull. His hands are bound behind his back. He is shaven, hairless, beardless. Vulnerable. He has the skin blemishes of all men, but the defining features of no-one. He has no need to call attention to himself; this act is not for showmanship. He closes his eyes and imagines the goal, the ones who have been and are to come – the whole of the human race, for whom he stands this day.

Context is everything. Standing alone in a room the sculpture has a lost and lonely look; the figure seems to be waiting for something to happen, and not really engaged in the events of this world. But this piece was originally displayed on the fourth, previously empty, plinth of Trafalgar Square. On the other three plinths stand General Napier, George IV on a horse and Major General Sir Henry Havelock, puffing out their chests and standing larger than life. Nelson, trapped atop his column, gazes out at the city. The glory of man, in war and lineage. The massive lions, with their cradling paws much loved by children wanting photographs of themselves, stare down the feasting pigeons. What would a Messiah do to break into this scene, to get himself noticed? Wallinger’s Messiah simply stands, teetering on the edge of his largely empty plinth, offering himself up to the choice of the masses. Worship? Mercy? Violence? …or indifference?

In Wallinger’s Christ I find my God again. It is a simple, elegant piece that captures the essence of the God-man that gave up his life. Not just his life-breath, but his life: his dignity, his freedom, his influence, his beauty. The lack of physical defining features enable me to find those features I love most – his overwhelming mercy and love, his humility and courage. Seeing that small figure against the backdrop of the self-important city reminds us of the God-perspective, and that little of what we think is important is really important. We must take time to behold the man, and behold the king.

Comments